Beginnings: DTA Research Seminar Series 2, Session 1

This research seminar took place in November 2022 at Staffordshire University, and as there were various technical problems with the recording of the presentation, I’ve transcribed it here. It’s written as if spoken rather than rephrased as a publishable conference paper, so will hopefully be an accessible read.

The ideas have moved on a bit since this point, but this represents my reasoning about the body of work at an early stage of development.

* * *

The topic of this seminar is about beginnings and how research topics get off the ground so I’m going to talk about a newish body of work – it’s actually a couple of years old but it hasn’t progressed particularly quickly – and talk about how the end of my PhD study went awry and what I did to turn that around and to move that forward into a new body of work.

My artistic practice and my research for the most part is to do with digital media, and the way that technology creates distraction and captures attention During the PhD I refined this as an area of study and produced a body of work that explored this area, and towards the end of the PHD I arrived at what I thought was a fairly succinct description of what I was about as a researcher:

My research was concerned with experiences of distractibility that are said to have emerged alongside the recent widespread adoption of digital communications technologies. Should compulsive engagement with digital media best be seen as information overload or is it a retreat into enjoyable technological distraction? How might the way digital systems are understood as data streams or cloud processes impact on the way we attend to them, or how they algorithmically attend to us?

(Text from 2018)

At the point that I was getting the final bits of practical work together for the PhD, I was looking at the idea of how digital media, particularly social media, becomes something that can be addictive and can create compulsion loops but as the PhD came to a close, I found the process of writing up enormously difficult. It was incredibly demanding, was taking up all of my waking time, and I was getting very burnt out and very stressed out. The last year of the PhD was spent doing nothing but writing and as an activity, that in itself can be… just a bit much, frankly.

I finally submitted the PhD in August 2018 and usually the viva is within six to eight weeks after submission, but for various reasons, my external examiner wasn’t in place in a timely way and the process seemed to just drag on and on. I didn’t actually complete my viva until May 2019, so there was an eight month gap between submission and viva, during which I was having to try and keep the contents of the thesis as alive as I could alongside my teaching role in order to be on standby for whenever the viva was actually called. This was a really hardcore experience: it was too much for me frankly, and by the end of it I was incredibly burnt out. Once the viva happened, I passed with minor modifications, and those minor modifications consisted of a single sheet of A4 which had a number of bullet points on it, and just one of those bullet points resulted in me having to restructure the whole thesis and add 120 extra pages of documentation. (Because the work I’d been doing was all digital, I’d done an online archive and the external examiner was of the view that it should be archived in print.) So, at that point, after all of that effort, and having to still carry out so much modification after the viva, I was left with the feeling that no matter how hard I work, I’m never going to be good enough for this. I reached the point where I just thought “what am I even doing…”. Also, by comparing myself to other people on the PhD program that I was on, found that other people seemed to be finding it easier. There were some people who joined and then had a comparatively straightforward experience on the PhD, and then progressed quite quickly post-doctorally, so by comparison I felt like I had just scraped through it. I felt like I didn’t really know what I was doing, I felt very negative about the whole thing, and essentially didn’t really feel that that I was part of academia or part of the art world that had got me into this.

It’s a common experience to be describing. I diagnosed this as imposter syndrome, and I wanted to find out a bit more about what that was all about. This initial research seemed to confirm that this was a thing that I was actually experiencing, and after doing a bit of overview research, I was looking for something that I could use as a literature review on the topic. I found this great chapter by Maddie Breeze which is called ‘Imposter syndrome as a public feeling [REF]’.When I read this quote, I thought “yeah, that’s me”:

“Feeling like an impostor involves the suspicion that the professional success of somehow been arrived at by mistake or achieved through a convincing performance, a deception. Imposter syndrome implies underlying feelings of inadequacy and deficiency but also conveys a particular felt-as inauthentic or fraudulent relationship to belonging and achievement.”

Breeze, M. (2018). Imposter Syndrome as a Public Feeling. In: Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (eds.). Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University. [Online]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 191–219. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64224-6_9. [Accessed: 6 November 2022]. p. 194

I thought that this described how I was feeling. This chapter goes on to discuss who is affected by imposter syndrome, and

“…how imposter syndrome is distributed in universities, and whether it is more common among minorities and those not marked as ‘elite’: non-traditional students and staff including women queer academics black academics, academics of colour, academics with a disability, first generations, working class academics, and academics with caring responsibilities”.

Breeze, M. (2018). Imposter Syndrome as a Public Feeling. In: Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (eds.). Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University. [Online]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 191–219. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64224-6_9. [Accessed: 6 November 2022]. p. 195.

The term ‘imposter syndrome’ emerges from feminist theory in the 1970s and, being aware that I do have the privilege of being white and male in the largely white and male dominated institution of academia, I was wondering whether it’s appropriate for me to be self-diagnosing as having imposter syndrome in this way. On reading this, it became clear that the way we understand imposter syndrome and the way it’s experienced is spread across a number of different types of social inequality, and there were some in the list that applied to me. I identify as a ‘first genner’, ie, the first of my family to have gone to University, as well as coming from a working class background, although it’s difficult to still claim that now while working as an academic. I was once working class perhaps, but maybe now that’s something that I feel less comfortable claiming as my current class identity.

What I think was important about this chapter was it allowed me to

“rethink imposter syndrome not as an individual deficiency or private problem of faulty self-esteem to be overcome but instead as a resource for action and a site of agency in contemporary higher education”.

Breeze, M. (2018). Imposter Syndrome as a Public Feeling. In: Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (eds.). Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University. [Online]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 191–219. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-64224-6_9. [Accessed: 6 November 2022]. p. 193.

This ties into some of the research that I was doing on the PhD. In the compulsive use of (for example) video gambling terminals, or social media, if you have a behavioural addiction, it’s easy to see that as your problem. It’s easy to see the addiction as a pathology that you inhabit, that you own, rather than looking at the fact that these are systems that have been acutely and carefully engineered to capture your attention and to keep you coming back and using them compulsively. The emphasis under neoliberalism is to focus on the individual as the site of pathology rather than reckoning with a structural situation that might be causing the pathology. All of this was very useful. It enabled me to start to think slightly differently about what it was that I was feeling and thinking and enabled me to refocus what I was doing practically in a slightly different area.

Towards the end of 2019 I did some what you might describe as ‘imposter syndrome informed teaching’. I did a lecture for the students which was called ‘the end of the future’, which looked at the collapse of the idea of progress in the 20th century and how even as late as 2019 it seemed unusual to think that the future would not be as good as the past. I think now with climate change and with the rise of authoritarianism and so on, it seems much simpler to accept that, but then, that sort of idea felt fairly wild and quite noteworthy.

As a consequence of that lecture, I started looking at Mark Fisher’s work on hauntology and thinking about how he describes the ‘nostalgia for lost futures’, but also the scope of his research: there’s one particular paper called ‘Good for Nothing’. It’s a blog post that he wrote about his own depression where he describes a book by David Smail about the ‘origins of unhappiness’.

The phenomenon I’ve just been talking about is what he describes as responsibilisation:

“each individual member of the subordinate class is encouraged into feeling that their poverty, lack of opportunities or unemployment is their fault and their fault alone. Individuals will blame themselves rather than social structures.”

Fisher, M., (2014). Good For Nothing. The Occupied Times. [Online]. Available from: https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12841. [Accessed: 6 November 2022].

He provides this great quote:

“the marks of class are designed to be indelible”

Fisher, M., (2014). Good For Nothing. The Occupied Times. [Online]. Available from: https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12841. [Accessed: 6 November 2022].

and that has for me had a bearing on how I am now thinking about my progression from working-class beginnings to a middle-class job and feeling out of place. All of this was good learning, and, by this point, I was starting to think I’m doing background research for something here. I don’t know yet what that something is, but this is different to what I was doing before.

I started to look at some of the environments that I had grown up in and that I’d experienced as part of my education and employment in the past.

This is my secondary school, Meadway Comprehensive. That’s the quadrangle.

This is Psalter Lane art college which used to be part of Sheffield Hallam University, and there it is being demolished.

Actually, my school’s been largely demolished as well incidentally…

And then here we are in Flaxman which hasn’t been demolished yet but I think Flaxman should be watching its back bearing in mind my track record of institutions demolished…

But reflecting on the spaces, the towns, the locations that I’ve been in they all have something in common architecturally: they’re made of concrete, they’re cheap, system-built brutalist buildings. There are certain types of concrete decoration which are designed to make them look nice but actually just make them look slightly more bleak.

I started reflecting on my own background, and the places where I was born and brought up. This is the Dee Road Estate which is to the west of Reading, and this image shows the whole extent of the estate, photographed near the end of its construction. It’s a very large new build showcase project that Reading Borough Council put together as part of the slum clearance activity that was going on in the late 1960s. It’s not of any particular architectural merit. It was designed to be a New Town development: mostly low rise with the intention of rehousing people whose houses would be compulsorily purchased on the other side of town and shifting the whole community over to here.

That photo contains of the entirety of my experience as a child. I was not allowed off the estate. We lived near the bottom corner and actually moved on to one of the houses in that vertical strip just to the left. Because that was the total range of my experience, it’s really deeply embedded in my experience of the world.

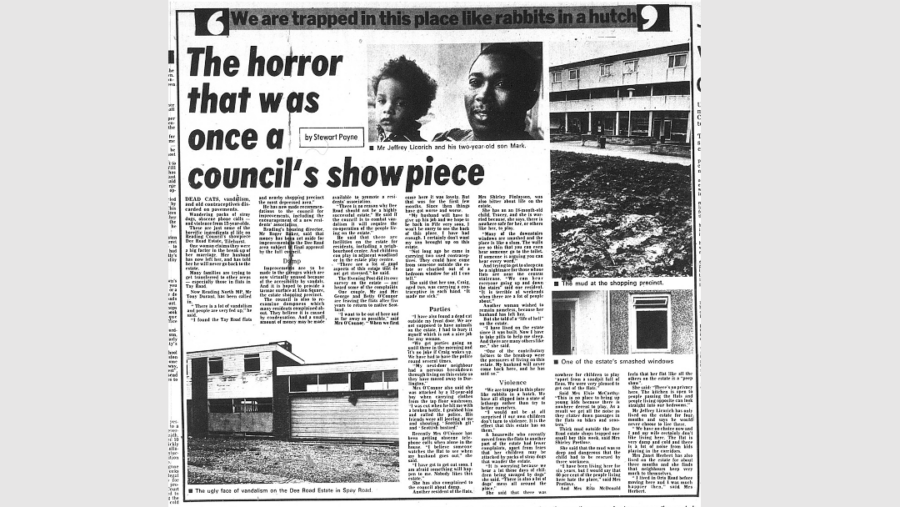

I started looking into the backstory of the estate. One of the things about this estate is that it has always been an area of very high deprivation. It’s got a very bad reputation and I think that after years of hyping up its construction as a showpiece project, the council were very upset to watch it fall from grace quite quickly after opening. I think that the council basically wanted it to go away. There’s very little archive material remaining. There’s not much research been done on it, and not much social history research done on it. It’s almost like everyone wants this to disappear, so I started making it not disappear. I started first of all by looking at some of the contemporary newspaper reports from the time it was constructed.

This is in the run-up to the construction of the estate: “Shaping a Showpiece… Reading’s Dee Road Estate”. Note that this is an advertisement feature that was put in the newspaper by the construction company.

“The Precinct Wakes” – one leg of the new L-shaped Precinct has been built.

“Relentless rain fell week after week”: this is building up the heroism of the construction company who built it and put it all together and then almost immediately it opened, literally weeks later, we’re finding in the same newspaper actual journalism:

Damp is making children sick, Council home unfit to live in, residents shun vandal-hit car parks.

So almost immediately the reality of the situation starts to reveal itself as soon as the adverting features are all done and dusted.

“The dream is our nightmare. With its symmetrical blocks, acres of concrete and stark uniformity, the Dee Road Estate is an architect’s Utopia. And that according to some of the women who live there is precisely what is wrong with the showpiece estate”

It’s true that it was constructed without facilities: there was no bus route running into the estate, there was no post office; initially there was no nursery. The whole thing seemed to be pushed out really quickly without being properly infrastructurally set up.

“The horror that was once a council’s showpiece”. I think the council and a lot of people in the town actually don’t really want this history to be remembered but a lot of other people are fond of the estate and remember their time there. Actually, quite a lot of the low-rise housing was fine, and it’s still standing and works really well. Some of the medium-rise housing didn’t last 15 years: it was demolished by the middle of the 80s.

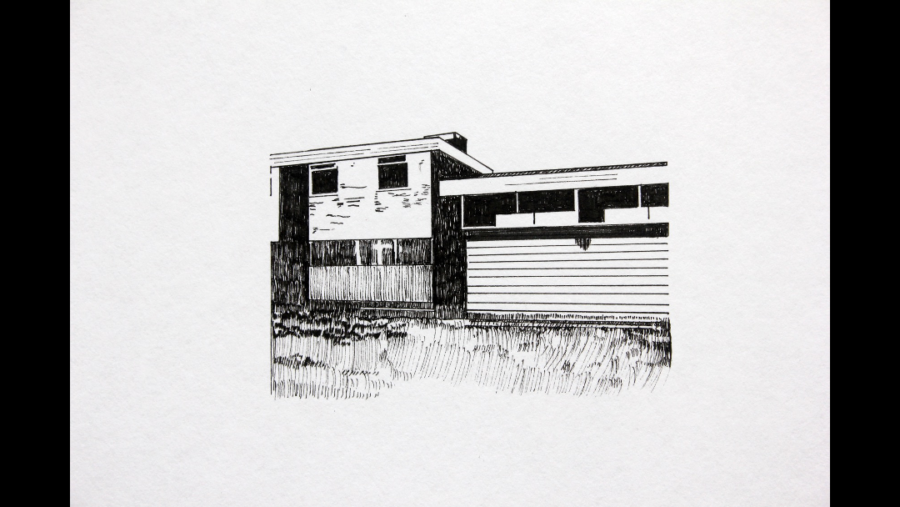

In terms of how this research turned into new work, I initially just started drawing: doing very tiny very detailed drawings of some of the images and some of the texts from the newspapers.

Drawing isn’t really my thing – I’m very much a software person, and I do digital artwork for the most part, and so doing drawings was like returning to the past in itself but also in the literal idea of drawing as ‘drawing near’: bringing something closer to you. That felt like an important aspect of this approach. Some of these are ink drawings some of them are pencil drawings. I’m not an especially competent drawer but it did feel like this was an important thing to be doing. All of these are taken from photographs in the local newspaper, and they’ve just been drawn in in pencil for the most part.

Moving on from the drawings, I also wanted to try and reconstruct parts of the estate and make models of them so I built this mould to produce versions of some of the decorative end faces that that adorn the ends of some of the concrete blocks, then using papier mâché and sort of squishing it in there.

What I had the intention of doing was building a model of the estate using similar methods as the actual estate: by using plates of concrete except it’ll be on a much smaller scale. The estate has this very distinctive design for the concrete plates which I’ve not seen anywhere else so that’s something that delineates it as this particular location. The edges of the model slide into each other in a similar way as the way that those concrete panels would have done. Some of these tests didn’t work but those failures were turning into photographic works as well. I was thinking about those as objects that might express something about collapse or fragility.

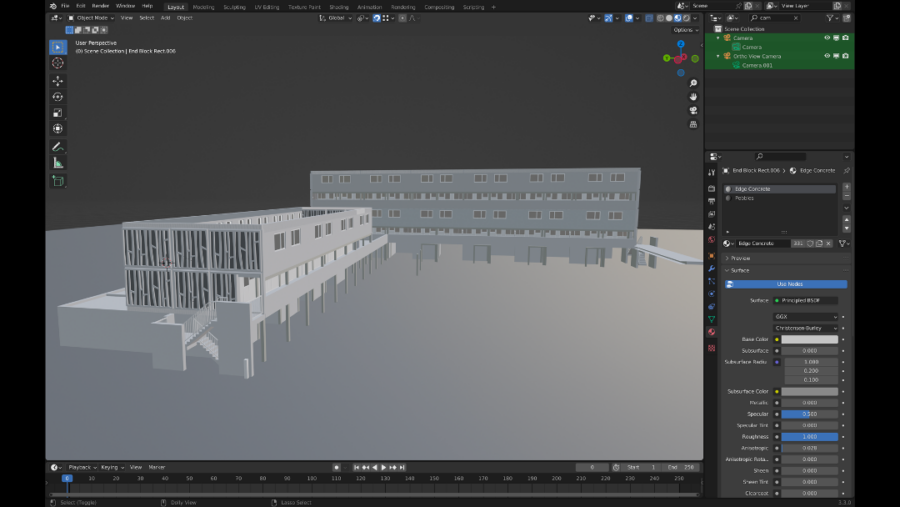

I also started to build a 3D model of the estate, which is taking ages because I need to learn how to use the software while I’m doing this, so it’s taken many, many months of work to get this far. Anybody with experience as a 3D modeller will probably be laughing at this, but I’ve been doing some very simple architectural visualisations of what the estate might have looked like when it was new.

The tree there is not authentic but everything else mostly is. These very flat very geometric very modernist compositions reflect something of the ethos of the initial utopian design of the estate before it all started to go a bit pear-shaped.

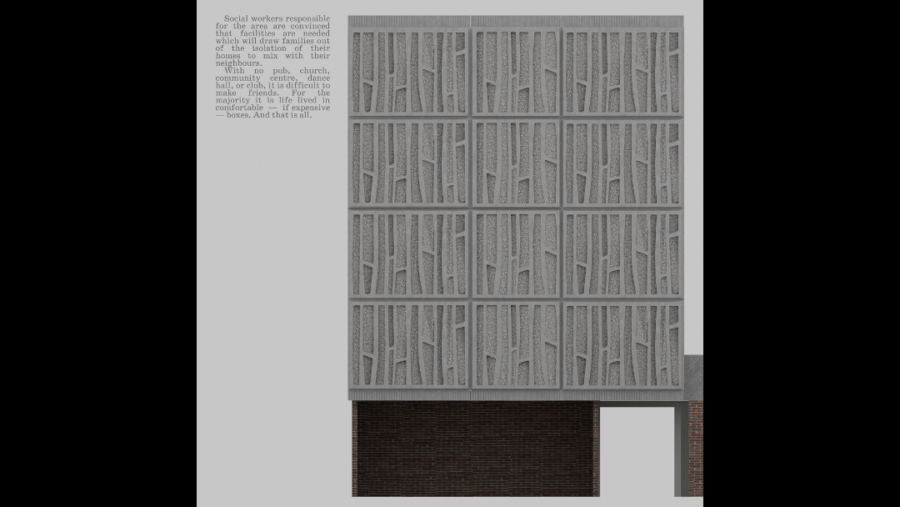

This is all work in progress and none of this has been exhibited. None of this has really made it into the public domain yet except through this talk, so there’s been a very slow burn for this project. It’s taken an extremely long time to get going. One of the other things I’ve been thinking about doing is bringing some of the texts from the newspapers into the compositions.

I’ll just very quickly read that one out: “social workers responsible for the area are convinced that facilities are needed which will draw families out of the isolation of their homes to mix with their neighbours. With no pub, church, community centre, dance hall or club, it’s difficult to make friends. For the majority it’s life-lived and comfortable if expensive boxes, and that is all.”

So that’s a quite a bleak summary of the situation, perhaps it’s slightly hyperbolically bleak from the local newspaper, but that’s the backdrop to where some of this work has been going.

To conclude, where the work is heading is toward a more wide-ranging critique of meritocracy. The moment of imposter syndrome and how I got through that was about the failure of the idea that if you work really hard you’ll do really well, and so critiquing that meritocratic view is quite an important thing for me to be thinking about. There’s a very good book that Beth from the Working Class British Art Network put me on to which is called Culture is Bad for You. It’s all about working conditions in the art world and in the cultural industries and that then leads on to a critique of social mobility through those skills.

In terms how you might deploy this approach, if we are to describe this process I’ve been through as a method, the takeaway is that satisfying your own curiosity is quite a good way to get started, and being self-aware and critiquing your own feelings of negativity can just open the door to something.

Breeze’s chapter speaks about working within and against academia and I’m extrapolating that into the art world. I need to know more about this. It’s a feminist strategy about being in a situation and working against it as well as being partially complicit in it. I think in the way Breeze describes it, there’s something in between fight or flight, so you’re not fighting or escaping it, you’re somewhere in the middle, and negotiating it. Also, for those who are interested in reducing barriers to participation in research in institutions like the one we’re in now, I think we do need to consider intersecting inequalities and figure out how those barriers can be removed and overcome.

References

Berardi, F.B., Genosko, G., Thoburn, N., Bove, A. & Thoburn, PhD.N. (2011). After the Future. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Breeze, M. (2018). Imposter Syndrome as Public Feeling. In: Y. Taylor & K. Lahad (eds.). Feeling Academic in the Neoliberal University. [Online]. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 191–220. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-64224-6_9.

Brook, O., O’Brien, D. & Taylor, M. (2020). Culture is Bad for You: Inequality in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Clance, P. & Imes, S. (1978). The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice. 15 (3).

Fisher, M. (2014). The Occupied Times – Good For Nothing. The Occupied Times. [Online]. Available from: https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=12841. [Accessed: 4 August 2020].

Smail, D. (2001). The Nature of Unhappiness. London: Constable & Robinson.